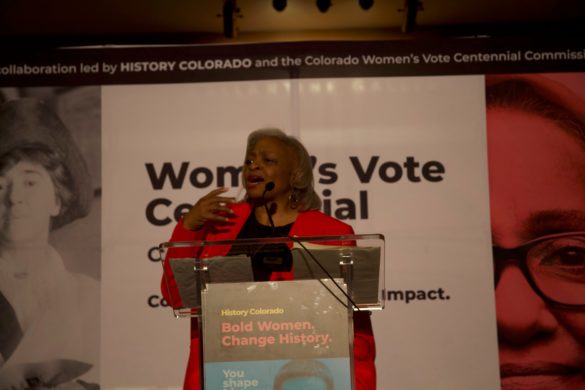

Sen. Rhonda Fields had no shortage of accolades when introducing the latest speaker in History Colorado’s “Bold Women. Change History.” speaker series, Carol Anderson. Anderson, an author and professor of African American studies at Emory University, spoke Feb. 12 about voter suppression and the history of America’s voter rights protections.

Anderson opened with the story of Maceo Snipes, who in 1946 was murdered by a group of white supremacists and political extremists in Georgia after casting his vote in the Democratic primary. “The message was clear,” she said. “You vote, you die.” Snipes was one of many who died, suffered or became the subject of extreme or inhumane persecution for attempting to vote prior to protective legislation.

“There is another kind of violence I want us to pay attention to,” Anderson said. “Bureaucratic violence.”

Mississippi lawmakers implemented a state constitution in 1890 that led to a disenfranchisement of primarily black Americans and largely prevented them from voting. “And remember, all of this is going to sound reasonable,” said Anderson before launching into what, essentially, the new laws meant for black voters.

The state imposed a poll tax that it said would help fund the expenses of voter stations, community outreach and mobilization efforts. The tax was roughly 2 to 6% of an average family income at the time, which left many low income, agricultural areas at too great a loss to be able to participate in elections. These areas are where “you have massive, systemic, endemic poverty,” said Anderson. The plan also imposed a literacy test, which Anderson pointed out would have been virtually impossible for black Americans to pass in the Jim Crow era of segregated education. The state made the argument that the literacy test would weed out any undereducated voters. When the U.S. Supreme Court heard the case against the Mississippi Plan in 1899, it let it stand because it found the wording of the laws was not inherently racist.

Anderson said that during this time, many black Americans fought against the system to try to register to vote. “Fannie Lou Hamer tried and got a Mississippi appendectomy,” Anderson said, referring to the case of a famed civil rights activist who, after making several attempts to register to vote, was given a hysterectomy without consent during an unrelated surgery under the state’s compulsory sterilization plan, which sought to decrease the population of black residents.

Anderson told the crowd that a reprisal came in the form of the Voting Rights Act of 1965. “[It was] the most effective piece of legislation that Congress has ever passed, so obviously it had to go,” said Anderson, and for decades, states fought and failed to remove the legislation. The act has been amended and updated with numerous provisions since its passing, an effort of lawmakers to prevent a repeal based on any discriminatory grounds.

Anderson said that today the primary methods of voter suppression are in the passage of “exact match” and voter ID laws and in largely unsubstantiated claims of “massive, rampant voter fraud.”

Cases of confirmed voter fraud over the last two decades are reportedly less than 50 individual instances out of billions of legitimate votes cast in numerous elections. In a study by Arizona State University, cases of election fraud outnumbered cases of voter fraud by more than 200%.

Anderson said exact-match laws are implicitly discriminatory as statistically, many typos and inaccuracies are present in records of black, Hispanic and Native American voter registrations. She said the likelihood of a missed or possibly impossible-to-enter character, like accent marks or tildes is much higher when entering information of voters with Hispanic names.

Similarly, she said that accents, apostrophes, hyphens and spaces in names can also get caught in the exact-match quandary.

Anderson said “this quiet civic death” is the threat we need to fear instead for our Democracy.

– Jess Brovsky-Eaker