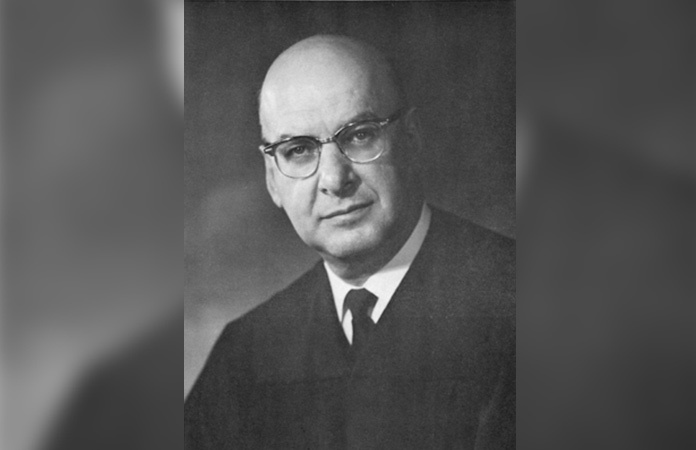

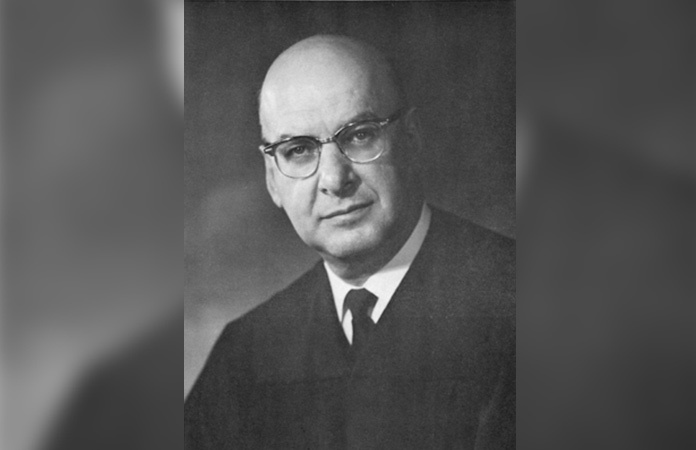

The U.S. District Court for the District of Colorado is housed in the Alfred A. Arraj Courthouse. Arraj, chief judge of the district court from 1959 to 1976, faced one of the most intense court backlogs in state history with more than 300 pending cases when he first took up the position. This is just a fraction of the backlogs caused by the COVID-19 pandemic, but the backlog plan he put in place in 1966 was just one of the many reasons the court quickly became a model for other courts to emulate, according to the court’s website.

Arraj got his start in law in the late 1920s. He got one of his first jobs with lawyer D.G. Reynolds in Springfield, Colorado and was quickly made a partner. The partnership and private practice he established lasted around 20 years. He served as Baca County Attorney part-time from 1936 until he served in the military in 1942.

According to his profile on the district court’s website, he served for 40 months, rose to the rank of Major and was awarded three battle stars before returning to civilian life at age 39. When he came back, he returned to his position as Baca County Attorney before being appointed deputy district attorney.

By the late 1940s, he confided in friends and colleagues that he wanted to become a judge. Arraj heard there would soon be a vacancy for a federal district court judgeship. He got the job in 1957 and was named chief judge by 1959 when the previous chief judge, Judge Knous, died unexpectedly.

While he was a judge, Arraj contributed to precedent-setting decisions including a constitutional issue at a university newspaper in February 1971. Arraj ruled Dorothy Trujillo “be reinstated in her position as managing editor [of the Southern Colorado State College Arrow] and refunded back pay,” the Chinook reported. Trujillo, who had been fired by the college administration after she published a “controversial” editorial condemning “the administration for proposing new faculty parking lots,” when she was required to submit all controversial materials to the faculty advisor before she was allowed to publish it. Arraj ruled “the state is not necessarily the unfettered master of all it creates. Having established a particular forum for discussion, officials may not set space limitations on that forum which would interfere with protected speech.”

Arraj also ruled in the historic and long-standing Blue River water case in 1977, following 28 years of litigation according to the Vail Trail. The dispute centered around access to water on the western slope and whether Denver needed to grant the water release from the Green Mountain Reservoir. The Vail Trail reported the secretary engineer of the Colorado River Water Conservation District said the City of Denver was allowed to store water of the Blue River in Dillon Reservoir as long as Green Mountain Reservoir, which served Western Colorado, was filled first. Arraj ruled Denver needed to release the water and an appeal of that decision was denied two years later.

In the face of his unexpected leadership of the court, Arraj rose to the challenge by devising an intense and ambitious trial calendar for all five district courtrooms in an effort to address the court’s towering backlog in the mid-1960s. In an innovative move for federal district courts, Arraj brought in judges from out of state to help hear cases, alleviating pressure on himself and the two other district judges. When the backlog was cleared, Arraj’s plan was used in other districts to address similar logjams in caseloads. “Among more than 90 federal courts, [the district court] was routinely near the top of the list in efficient use of jury time and in providing prompt trials in both civil and criminal cases,” the court’s website states.

Arraj served on the court for 35 years. He took on senior status in 1976 but continued to work every day for the court until two weeks before his death in October 1992 at age 86. Eight years later, Congress named the new federal courthouse in Denver after Arraj.