In his first dissent for the state’s highest court, Colorado Supreme Court Justice Carlos Samour delivered a rebuke of the majority’s holding in Casillas v. People that an unlawfully collected cheek swab of a juvenile offender should be suppressed as DNA evidence later used to convict the same person of an unrelated crime.

In the underlying case, petitioner Ismael Casillas had his cheek swabbed by a juvenile probation officer to collect his DNA. But the DNA collection violated the Colorado statute governing deferred adjudication of juvenile offenders because under they law they typically do not have to submit to a DNA sample.

Months after Casillas fulfilled the terms of his deferred adjudication and his juvenile case was dismissed, his DNA was used to link him to a carjacking. Casillas requested suppression of the DNA evidence in his trial because the probation officer had collected it unlawfully, violating his Fourth Amendment rights. The trial court denied the motion, and Casillas challenged the suppression ruling on appeal.

The parties have not disputed that the cheek swab done by Casillas’ supervising probation officer constituted an illegal search under the Fourth Amendment, and also violated Colorado law that exempts offenders such as Casillas from submitting DNA samples. The Court of Appeals made the same conclusion. But the court nevertheless upheld the suppression ruling in 2015, holding suppression was not appropriate because the juvenile probation officer performed “nothing more than a supervisory function under the direction of the juvenile court,” and moreover, suppression “would have no deterrent value” for future violations of protections against unlawful searches. Suppressing evidence from illegal searches by law enforcement is intended to deter police misconduct, and courts must weigh the benefits of allowing the evidence against the possible harm it could cause.

But the Supreme Court cited three main factors in overturning the Court of Appeals ruling. The court disagreed with the People’s reliance on precedent cases that involved law enforcement officers reasonably relying on information to conduct searches provided by third parties that later proved inaccurate. In those cases, police did not have reason to question the validity of the information they relied on, and so suppression of resulting search evidence would not serve to deter future police misconduct.

“Nothing in the record here, however, suggests the juvenile probation officer who performed Casillas’s cheek swab did so in reasonable reliance on misinformation provided by a third party,” wrote Justice Monica Márquez for the majority. “The error giving rise to the unlawful search and seizure was not attenuated; suppression here would target the officer’s own mistake, not someone else’s.”

Márquez wrote that juvenile probation officers are more akin to law enforcement adjuncts than judicial officers or court clerk employees, because they have broad powers to enforce laws, take juveniles into temporary custody and execute arrest warrants.

The Supreme Court also disagreed with the Court of Appeals’ reasoning that Casillas’ supervisory probation officer was only performing a supervisory function. The Combined DNA Index System to which Casillas’ sample was uploaded exists to allow law enforcement to identify suspects in crimes through profile matches. Moreover, reasoned the court, a cheek swab for the purpose of collecting a DNA sample for the CODIS database serves an “inherent law enforcement purpose.”

The office of the public defender, which represented Casillas, could not be reached for comment by phone. Its website has a posted statement saying it is the office’s policy and practice not to comment on pending litigation. A spokesperson for attorney general Cynthia Coffman’s office did not return a request for comment.

Samour’s Dissent

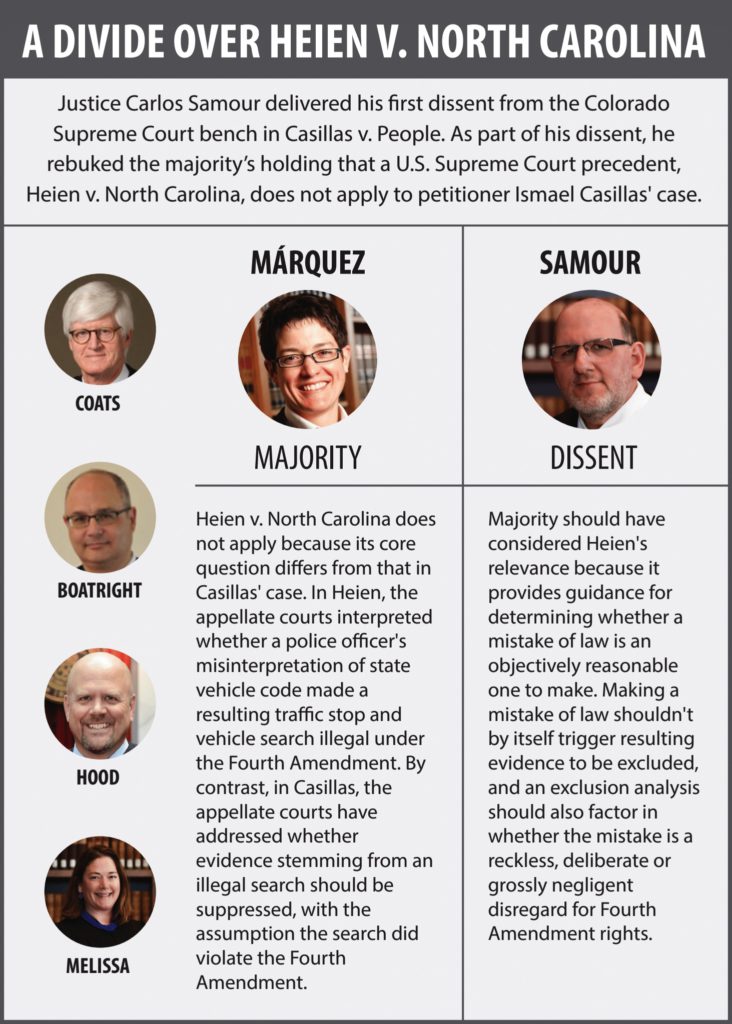

Samour’s 20-page dissent equaled the length of the majority’s opinion. He took issue with the majority’s implied conclusion that the juvenile probation officer’s mistake of law was not objectively reasonable. He also disagreed with the holding that suppression of the DNA evidence would have its intended deterrent effect. Samour wrote he believes the majority mistakenly disregarded the importance of Heien v. North Carolina as precedent.

That case, which ultimately went to the U.S. Supreme Court, addressed whether a traffic stop based on a police officer misunderstanding the law violated a motorist’s Fourth Amendment rights. A police officer pulled over a motorist who had one nonfunctional brake light. The motorist consented to a search of his vehicle, and two officers found cocaine in his car. Before trial for cocaine trafficking charges, the defendant filed to suppress the evidence uncovered through the search, contending the stop and search violated the Fourth Amendment.

That case, which ultimately went to the U.S. Supreme Court, addressed whether a traffic stop based on a police officer misunderstanding the law violated a motorist’s Fourth Amendment rights. A police officer pulled over a motorist who had one nonfunctional brake light. The motorist consented to a search of his vehicle, and two officers found cocaine in his car. Before trial for cocaine trafficking charges, the defendant filed to suppress the evidence uncovered through the search, contending the stop and search violated the Fourth Amendment.

The North Carolina Supreme Court concluded the police officer had misinterpreted the state’s vehicle code, which the court found required only one functional brake light. But even so, the court concluded the officer’s traffic stop was lawful under the Fourth Amendment because his misinterpretation of the vehicle code was reasonable.

The Colorado Supreme Court concluded the Heien case did not apply to Casillas’ case because its core question differs. By contrast to Heien, in Casillas, the appellate courts have made the assumption the search in question did violate the Fourth Amendment in addressing whether evidence stemming from an illegal search should be suppressed.

Had Casillas been sentenced to probation rather than receiving deferred adjudication, he would have been required to submit a DNA sample. Instead, he was ordered supervised by the probation officer. Samour recognized the difference in meaning between “sentenced to probation” and being “ordered supervised” by probation is so nuanced that the confusion was an objectively reasonable mistake, made by both the probation officer and the trial court when denying Casillas’ evidence suppression motion.

“Although the majority gives Heien short shrift, the Supreme Court’s analysis is instructive in assessing the reasonableness of the juvenile probation officer’s error of law,” Samour wrote. “Just as it was reasonable for the officer in Heien to think that the North Carolina traffic code required two functional brake lights, it was reasonable for the juvenile probation officer to think that subsection (1)(e) required Casillas to submit to the collection of a biological substance sample.”

In the final section of his dissent, Samour took issue with the majority’s holding that DNA evidence suppression would serve a deterrent purpose in Casillas’ case. The majority argued not applying the exclusionary rule would create an incentive to collect DNA from every juvenile person whether lawful or not because law enforcement “would benefit from the ability to identify more suspected perpetrators of crimes if the database were more comprehensive” and there would be no “risk that unlawfully obtained evidence would be excluded from future criminal prosecutions.”

“Respectfully, I am unmoved by this sky-will-fall contention,” Samour wrote and, citing Heien, continued, “The majority forgets that ‘[t]he Fourth Amendment tolerates only reasonable mistakes, and those mistakes—whether of fact or of law—must be objectively reasonable.’”

— Julia Cardi