With secret workplace recordings showing up in nightly newscasts and high-profile lawsuits, employers are perhaps more interested than ever in maintaining policies that restrict workers from capturing conversations.

The question has often been whether those policies were lawful. But the National Labor Relations Board has recently relaxed its position against employers that enforce no-recording policies on their premises. This comes as the general public sees just how much of a stir sensitive employment-related recordings can create when released to the media.

Earlier this month, former White House aide Omarosa Manigault Newman released a recording of her firing by chief of staff John Kelly, and she has suggested she has many more surreptitious tapes from her time in the White House.

As employment litigators know well, secret workplace recordings often end up playing a significant role in employees’ legal claims. Elsewhere in the federal government, a Federal Housing Finance Agency employee secretly recorded a conversation with the FHFA director in which she claims the director made advances toward her while considering granting her a pay raise, NPR reported Tuesday. The tapes are cited in the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission’s harassment, retaliation and pay discrimination claims against the agency.

The national news exposure of secret recordings underscores the reality of the modern workplace: employees are taping more and more conversations. And employers are concerned about it.

“I get calls about this issue regularly,” said Veronica von Grabow, an employment attorney and principal at Jackson Lewis in Denver. Sometimes employers will ask her for counsel because they have decided to review their workplace recording policy, but more often the issue comes up because they know or suspect an employee to have a sensitive recording and want to know what the company’s rights are as they respond.

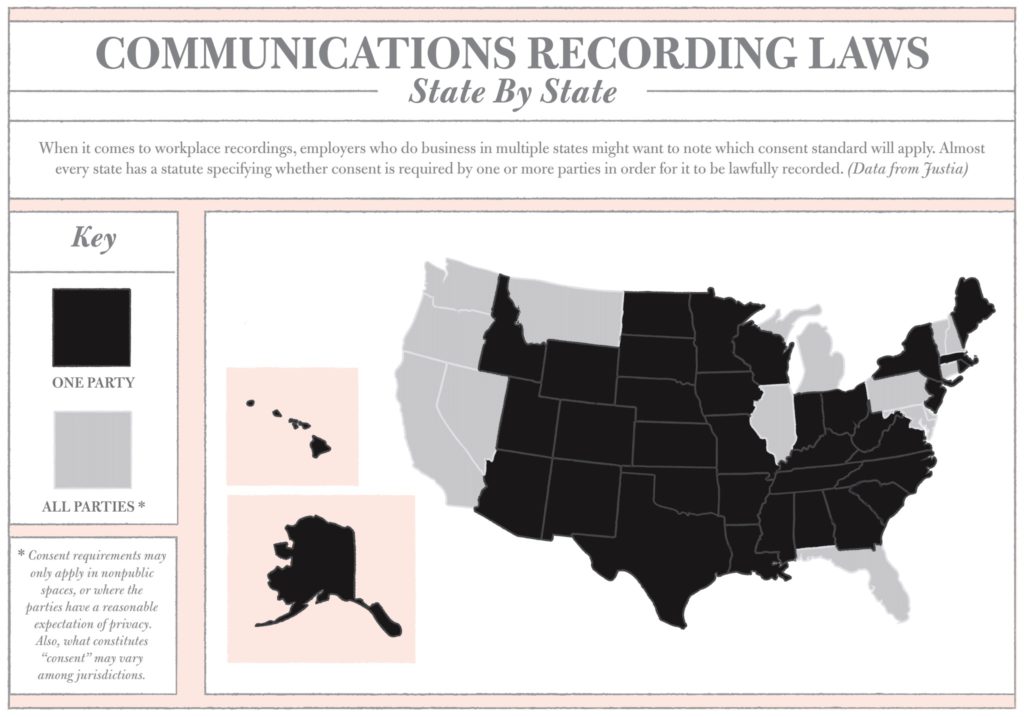

Under federal law, as well as in 38 states that include Colorado, it is generally legal for a person to record conversations they’re party to without the other participants knowing. Secret recordings may be unlawful in states like California that require all parties to consent to the taping, however — a fact that employers might be mindful of if they operate in states besides Colorado.

But even in Colorado, there are circumstances where a workplace recording might be unlawful. Von Grabow knows of a company that had an employee try leaving a phone in a common area to record conversations. Since the employee wasn’t present for those conversations, the recording didn’t even satisfy Colorado’s one-party consent requirement.

Steven Gutierrez, a labor and employment attorney who is a partner in Holland & Hart’s Denver office, tends to recommend that employers ban workers from secretly recording workplace conversations because such a ban “provides comfort to employees and management that they can have open dialogue … and you don’t want to stifle that discussion.” The specter of secret recordings can cause managers to walk on eggshells around employees and avoid candid, non-scripted conversation with them, he added.

Employers have also restricted unapproved recordings of work meetings as part of protecting against trade secret theft, as those conversations might deal in proprietary information that an outgoing worker might try to take with them to a competitor, Gutierrez said.

Employers recently received the NLRB’s go-ahead to enforce no-recording rules. Previously, the NLRB would generally find it unlawful for an employer to ban its workers from recording conversations, phone calls, images or meetings without company approval. That was based on its standard set in the 2004 decision Lutheran Heritage Village-Livonia, where the board held that even if an employer’s workplace rule was neutral to the National Labor Relations Act on its face, it violated the statute if a reasonable person could still construe that it prohibits union organizing or other NLRA Section 7-protected activity.

The NLRB reopened the door to no-recording rules in December when it set out new lawfulness standards for workplace rules in its Boeing decision. No-recording policies fall into a category of rules that are generally lawful for employers to have on their books; they can’t be reasonably construed to violate NLRA rights, and the potential adverse effects of the rule are outweighed by its justifications, the board held.

NLRB General Counsel Peter Robb reinforced the lawfulness of no-recording rules in a June 6 memo. Employers, Robb wrote, have a legitimate interest in restricting recording on their premises, which include “security concerns, protection of property, protection of proprietary, confidential, and customer information, avoiding legal liability, and maintaining the integrity of operations.” Limiting secret recordings “can also encourage open communication among employees,” Robb continued.

Hanging over the NLRB’s reversal on workplace recording bans, however, is a federal appellate decision against Whole Foods in June 2017. In that case, the 2nd Circuit Court of Appeals upheld the Obama-era NLRB’s position that such bans could chill Section 7-protected activity. After that ruling, many employers revised their workplace recording policies to explicitly state that they were in no way intended to infringe on workers’ NLRA rights, Gutierrez said. He noted, however, that the Whole Foods decision didn’t prohibit no-recording policies across the board, so there was room to have a legal one even before the NLRB’s recent green light.

Before employers rewrite their policies to take a hard line against workplace recordings in light of the NLRB’s Boeing decision, they should try to “strike a balance with it right now because the issue is in such flux,” von Grabow said. The legality of those policies is still subject to change in the years to come with potential new court decisions or shifts in NLRB leadership, she added.

Gutierrez said it’s not just the ubiquity of smartphones that has made workplace recordings by employees more commonplace. “I think there perhaps has been a decline in the trust factor that exists between employees and employers.”

Von Grabow said it’s hard to tell if the relationship between workers and management is necessarily to blame for the frequency of workplace recordings. But the growing ease of capturing others’ behavior on tape is an undeniable factor. “The ability to record conversations is so readily available now,” she said. “We’re just seeing that trickle into the workplace.”

— Doug Chartier