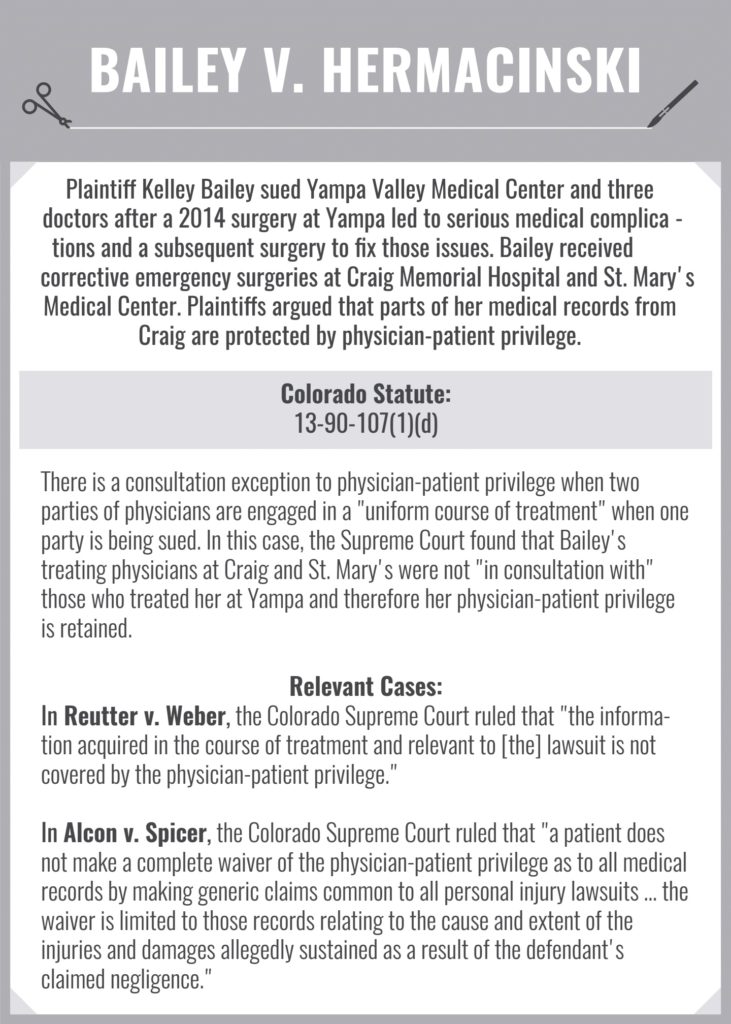

In March 2014, Kelley Bailey had a hysterectomy at Yampa Valley Medical Center. She returned to the hospital in July with abdominal pain and received a second surgery performed by Dr. Mark Hermacinski and Dr. Leslie Ahlmeyer. During the second surgery, Bailey argued, the defendants perforated her bowel, which led to a third emergency surgery at Craig Memorial Hospital a few days later. Bailey had multiple surgeries afterward at St. Mary’s Medical Center to correct the complications and sued the doctors for medical negligence.

The defense sought to interview several doctors at Craig and St. Mary’s who treated Bailey after the second surgery. Plaintiffs filed a motion for a protective order to block these interviews from being held without Bailey’s counsel present. They argued that the providers had residually privileged information that was redacted from Bailey’s medical history. The defense claimed there was no evidence that those physicians had privileged information outside of the scope of the negligence claims.

Plaintiffs argued to the trial court that the protective order was necessary to avoid “undue influence,” contending that “there appears to be a concerted effort by the malpractice insurers in Colorado, specifically COPIC, to hire counsel for treating physicians who are not potential defendants in lawsuits.” COPIC insures all the defendants in the suit. Counsel for the defense declined to comment on the case.

Colorado statute includes an exception to physician-patient privilege when that physician is sued, and a 2007 Colorado Supreme Court decision in Reutter v. Weber extends that exception to non-party providers who are “in consultation with” other providers who have been sued.

In this case, the trial court found that the physicians from Craig and St. Mary’s were engaged in a “uniform course of treatment” for Bailey and the exemption to the physician-patient privilege applies here. The defense argued that because Bailey brought a claim for damages based on the surgery complications, she impliedly waived her privilege with the physicians who treated her afterward, and the trial court agreed. The trial court also allowed ex parte interviews with the Craig and St. Mary’s doctors, a move that the Supreme Court said was an abuse of discretion.

The Supreme Court disagreed on the consultation piece. It asserted that Bailey’s communications with the other physicians were all privileged. The plaintiffs and several amicus briefs asked the Supreme Court to consider reworking the ruling in Reutter, but the court declined.

The case was remanded for the trial court to determine whether Bailey impliedly waived her physician patient privilege doctrine. A 2005 ruling in Alcon v. Spicer found that a waiver of physician-patient privilege “can be implied through a patient’s conduct as well as obtained by express authorization to the release of information.”

The court also asked the trial court to reconsider “whether there is any risk that ex parte interviews with the non-party medical providers would inadvertently reveal residually privileged information, or defendants would exert undue influence on the non-party medical providers in the course of any ex parte interviews.”

The plaintiffs’ brief to the Supreme Court included affidavits from physicians to illustrate their argument that undue influence occurs. Schoenwald & Thompson partner and plaintiff’s attorney Julia Thompson argued that after treating physicians are provided with COPIC counsel, “their previously favorable standard of care and/or causation opinions for the plaintiff are changed.” The defendants argued that “treating physicians have a due process right to the assistance of counsel, even if they have not been named as defendants.”

The court also ruled that before a request for ex parte meetings is granted, the trial court must determine whether the Craig and St. Mary’s doctors “could be subject to undue influence during those ex parte interviews.”

In Samms v. District Court, the Colorado Supreme Court ruled on the issue of implied waivers and decided that a patient’s consent could be implicit or explicit.

The ruling also established a framework for ex parte interviews: the waiver must apply, and the significance of the risk of privileged information disclosure must be shown. Plaintiffs argued to the Supreme Court there was a high risk of privileged information and, therefore, counsel should be present for ex parte interviews.

Thompson said a number of trial courts have ruled that different safeguards should be implemented in ex parte interviews to protect privileged information but also to prevent undue influence. She advocated for the meetings to be recorded or a letter to be sent to the physician in advance of a meeting with the defense.

Thompson says she’s seen both implicit and explicit bias come into play in cases where one physician sees a colleague being sued and attempts to help them somehow, or where there have been attempts to convince a physician to give testimony that helps the defendant.

“Those are the issues that happen when this is done in secret,” she said. “The plaintiff’s perspective is these physicians are somebody with whom the plaintiff already has a relationship, and meeting with them on an ex parte basis can irreparably harm that relationship.”

—Kaley LaQuea