The U.S. Department of Justice favors its cooperation program for foreign bribery cases enough that it wants to apply it to other white-collar criminal matters.

In a March 1 speech at the American Bar Association National Institute on White Collar Crime, DOJ Criminal Division Head John Cronan said the department will expand its program that allows companies some leniency when they self-disclose certain violations. Previously, the DOJ had piloted, and then made permanent, a regime under which it would give corporations credit when they come forward with Foreign Corrupt Practices Act violations. But the department is now willing to offer self-disclosure credit for criminal violations besides those under the FCPA.

The announcement puts another option on the table for corporations that suspect wrongdoing in their midst but want to minimize the penalties they could face from the federal government. But the decision to come forward with potential corporate crimes remains a complicated one, and the DOJ’s standards can be difficult to meet, say white-collar defense attorneys.

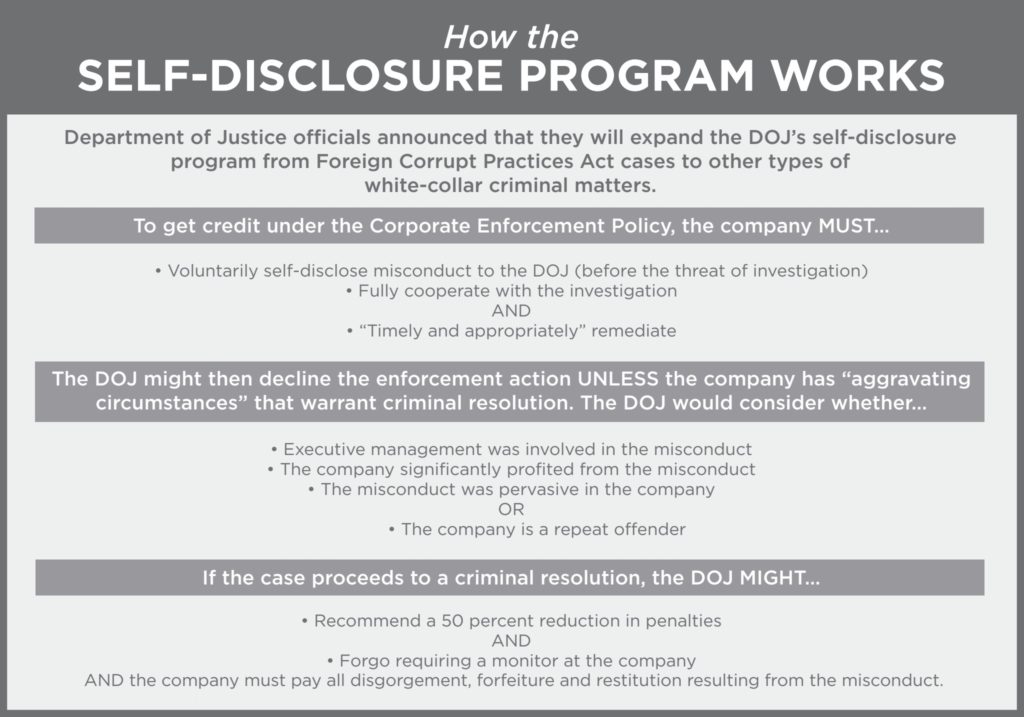

The DOJ currently offers benefits to companies that have “voluntarily self-disclosed misconduct in an FCPA matter, fully cooperated, and timely and appropriately remediated, all in accordance with [certain] standards,” according to its FCPA Corporate Enforcement Policy. The department might decline to prosecute the self-reporting company depending on “the seriousness of the offense or the nature of the offender.” In order to qualify for leniency, the company must also pay all disgorgement, forfeiture, and restitution from the wrongdoing.

This program doesn’t apply to the Securities and Exchange Commission, which also prosecutes FCPA violations, though generally not as many. Last year the SEC filed eight new FCPA enforcement actions while the DOJ filed 24.

The DOJ piloted these self-disclosure guidelines in April 2016 and formally adopted them in November as its FCPA Corporate Enforcement Policy.

“We analyzed the Pilot Program and concluded that it proved to be a step forward in fighting corporate crime,” Deputy Attorney General Rod Rosenstein told attendees in a November 28 speech at the International Conference on the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act. “We also determined that there were opportunities for improvement.”

In the pilot program’s first year, the DOJ received 22 voluntary disclosures, up from 13 during the previous year, Rosenstein said. But since rolling out the program, the department has clarified the type of credit a company stands to receive for self-disclosure as well as its requirements for getting it.

The DOJ issued seven FCPA declinations in the program’s two years. The most recent declinations were for engineering and construction firm CDM Smith and oil and gas company Linde North, both in June.

While declination is the presumed goal for self-reporters, the DOJ may still proceed with criminal charges. When it does, it will often push for the qualifying company to get up to a 50 percent reduction in fines. It will also decide against placing a monitor with the company if the company installs an effective compliance program.

The March 1 announcement to expand the FCPA program “represents a desire on the part of the department to test the waters” in other types of matters, said Tyler Coombe, a shareholder at Greenberg Traurig whose practice focuses on FCPA defense and investigations. He said it’s fair to interpret that the DOJ is pleased with the outcomes it’s gotten from the FCPA program.

The question is how the self-disclosure-for-credit scheme might work in other types of white-collar criminal matters. Mike Theis, a partner at Hogan Lovells who focuses on False Claims Act litigation, said “it’s hard to tell at this point how significant this [expansion] is going to be” to other areas of white-collar defense. But it does continue a trend in DOJ white-collar crime enforcement, he said, which is to reward self-reporting, cooperation and remediation. And it certainly isn’t a negative development for companies.

“If I’m in this situation, I want have as many of these tools as possible to argue for declination or reduction in penalties,” Theis said.

Even so, corporations and their counsel must weigh the myriad risks and determine what benefits the company stands to gain from coming forward with violations.

“[Self-disclosure] continues to be a very complex process and a difficult decision to make. That hasn’t changed,” Coombe said. But by spelling out the potential incentives for coming forward, the federal government has “changed the landscape [of that decision] a little bit” and made the prospect of self-disclosure more enticing, he added.

But there remain potential downsides to self-disclosure. “Reputational risk is a big one,” Coombe said. Resolving the criminal issue then becomes a public process rather than strictly internal. It can take a long time, be disruptive to the company’s operations and become expensive to initiate the DOJ’s process, he added. “It’s still a pretty bumpy road to travel, and it’s a decision not to be taken lightly.” Still, a lot of companies have chosen to do it and many have had a good outcome, Coombe said.

Theis said that before a company discloses a possible violation, it has to confirm whether the DOJ would see it as a “true volunteer” — that the company can genuinely say it had no idea it was already under government investigation. “That’s a pretty significant factor,” Theis said, since if a company isn’t a true volunteer, it forfeits the chance at declination under the program.

In the False Claims Act proceedings that Theis handles regularly, companies often don’t know they’re under investigation because whistleblowers can bring FCA allegations to the DOJ under seal. But a self-disclosing company might still get some credit even if an FCA whistleblower has already come forward, Theis said.

In announcing the policy expansion, DOJ officials mentioned their recent resolutions of the Barclays PLC and HSBC securities fraud cases. On Feb. 28, the department declined to prosecute Barclays for securities fraud, citing its self-disclosure and cooperation. HSBC, on the other hand, was hit with a $63 million criminal penalty in January under a deferred prosecution agreement with the DOJ, and in a similar case as Barclays.

“That’s a specific example that they seem to be highlighting as if to say, ‘Who do you want to be?’ ” Theis said. “ ‘Do you want to be Barclays or do you want to be HSBC?’ ”

—Doug Chartier